Glamorising the Struggle

My life is a romcom except no, it isn't, and should I post myself crying online?

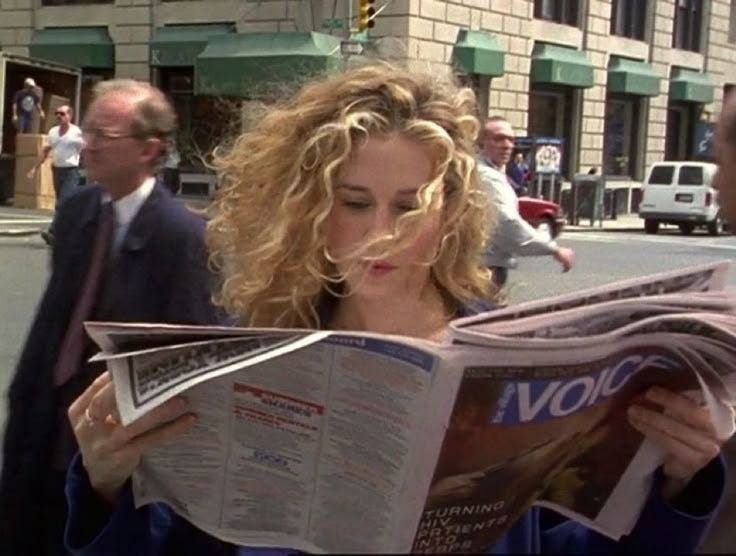

My life is a romcom!! I’m its leading lady!!

I am in my mid-twenties and live in New York City. How unbelievably cool is that to say. I moved here from Paris and work in Luxury, which means I get to wear fun outfits to my almost-exclusively female office. I boast of a wardrobe overflowing with beautiful vintage pieces I’ve spent years curating, each holding entire stories of their own. I cook and dance in my dressing gown almost every night. I write whatever I want to in my digital publication for over a thousand of the most gorgeous readers (hello & thank you, yes you <3). I love print media and have made it one of my many personal soapbox causes to support (alongside public libraries, inner-city volunteering, and so on). I have made incredible friends all over the world, and I’ve just started writing letters to keep more meaningfully in touch with many of them (inspiration directly from Julianna: so you wanna bring back snail mail). I have a hopeless (but determined) love life. I cycle to work year-round, huffing and puffing in everything from cashmere and coats to silk shirts and skirts, which often lends me a slightly frazzled air. I live in the most perfect, most “me” studio apartment (red brick wall and all), which I have furnished almost-entirely second-hand. It even has the most quintessential New York fire escape with a view of the Empire State Building, but I’m bragging now. In short, I often feel like my life has a cinematic edge that lends itself favourably to the romcom persuasion.

But also, I am tired. Not the kind of exhaustion that feels as if it has seeped into your very bones, but in the sense of perpetually craving a deep, long, all-encompassing hug. I get enough sleep, I eat well, I socialise, I exercise, but I also spend my entire day feeling on the verge of losing it.

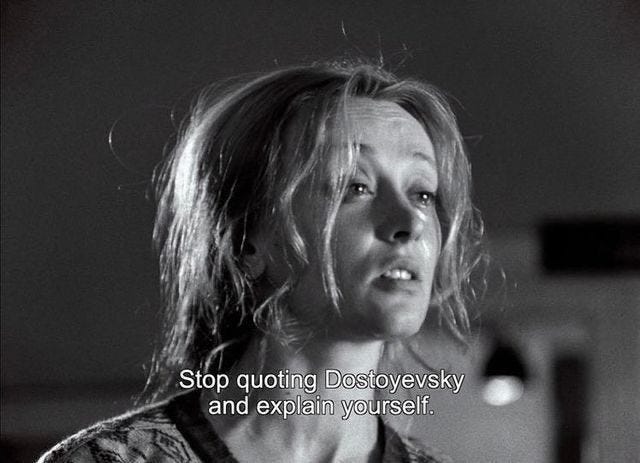

Almost every woman I have ever met has a secret belief that she is just on the edge of madness, that there is some deep, crazy part within her, that she must be on guard constantly against ‘losing control’ — of her temper, of her appetite, of her sexuality, of her feelings, of her ambition, of her secret fantasies, of her mind. — Elana Dykewomon, “Notes for a Magazine,” Sinister Wisdom #36 (Winter 1988/89).

I am on the cusp of unemployment, coming off a fixed-term contract [something that is becoming increasingly common for my severely struggling industry (Fashion/Beauty/Luxury)] that will end in the first week of April. I am sick of earning the lowest salary out of almost all my friends in the city and scrutinising every penny that comes into and out of my bank account. I miss my family constantly and am less and less able to contain the flare of resentment that spikes each time I meet someone in the city whose siblings live nearby or whose family lives in a neighbouring state (I swear its 95% of the people I know here). [Side note: no wonder Americans think New York is the greatest city in the world if they get to leave it every few weeks to see their families who all live within a three-hour-commute radius and are on the same time zone]. Sometimes, it takes me hours to fall asleep at night because I am spiralling about how many important moments I am missing in my friends’ and family’s lives by living abroad. I haven’t seen any of my grandparents in years. I don’t have a home in any traditional sense of the word and my family all live in different countries. I care about everything more than I probably should. Despite my hardest efforts, I am almost always thinking about how I am being perceived. I think you’d agree that all of the above is distinctly un-leading-lady-like.

Growing up positively obsessed with romcoms, I consider myself a connoisseur of sorts and have always harboured a secret, vain desire to treat my own life as one, of which I am the enigmatic leading lady. While much of this attitude can be healthy and productive (main character energy and all that), it can also make everything suddenly feel very confusing and overwhelming when life starts to veer off the path of the glamorous protagonist with her perfect job, apartment, friendship group, routines, and quirks, and morph into something more closely resembling a real person with real ups and downs and in-betweens.

To glamorise or to deinfluence, that is the question. Consuming social media in the post-pandemic landscape is an exercise in digesting extremes. One after another after another: ‘spend the day with me as a [glamorous sounding dream job] living in [city people dream of visiting]’, ‘come with me to buy [another luxury bag]’, ‘realistic day in my life’, ‘deinfluencing: five of my worst purchases this year’, ‘get ready with me while I tell you about how I’ve actually been doing’ et cetera.

Similarly, has anyone else met their friends’ boyfriends for the first time (after previously only consuming the relationship through curated IG photos and charming anecdotes) and been horrified by how boring or weird [derogatory] he was in comparison to her? It is only after the relationship ends that the glamour comes off and said friend begins her deinfluencing campaign, setting the record straight and revealing truth after horrifying truth about how imperfect and fraught their relationship was in actuality. It seems that we have become so used to operating in extremes that we frequently glamorise entire relationships, jobs, cities, and experiences to the point of fallacy.

The threshold between glamour and illusion is etymologically evasive. Especially as it relates to the expression of struggle.

I, for one, am currently struggling to balance my ambitions with an insanely shitty job market, financial independence with dwindling savings, and homesickness with my love for living abroad, amongst other things. People who know me in real life know these things, but my digital footprint tells a different, slightly more glamorous story.

But if I didn’t glamorize my own struggle, where would I be? With just the struggle, that’s where. So what I want to say is, no, I would never glamorize anyone else’s struggle. But I do often see friends of mine who are writers and artists glamorizing their own struggles, and I think we’re allowed to do that. Because sometimes glamour is all we have, and while it doesn’t substitute for health insurance, it can in fact make the struggle easier to bear. We all get to have our own coping mechanisms, and glamour is one of mine.

When we glamorize the struggle, we make it seem less hard, but of course really it’s not, right?

So when I feel most in the struggle, when I feel most down, most filled with self-doubt, that’s exactly when I tend to glamorize the most. That’s when I put on a long, swooshy skirt and walk through the city as though I owned it: yes, all the streets and the trees and the leaves that have fallen. That’s when I start to tell a story about myself in which I do, indeed, glamorize the struggle. Because if I didn’t have that, what would I have? Just the struggle.

Glamour is one of the tools of the writer, and I would say the artist in general. Glamour is actually the essence of what we do: we change not reality, but perception. We are spell-casters, all.

I don’t have a clear answer as to whether or not we should. After all, Emily Dickinson’s and Vincent Van Gogh’s struggles were real and painful. And yet out of them came the most glorious art. What I do know is that I sometimes glamorize my own, and I think that’s all right. If I didn’t, I would be a lot less sane, and I would have a lot less fun. I wouldn’t walk through the city in a swooshy skirt, feeling like the heroine of my own novel, telling a story about myself as much as I tell a story about any of my other characters. I do think it’s important to be honest about the struggle, about how much sheer work goes into the making of art . . . But it’s also all right, I think, to glamorize at least your own struggle every once in a while. If I didn’t, it would make the struggle so much more of a struggle, you see.

Years of presenting our lives as effortlessly shiny and perfect have led to collective demands for authenticity, but portraying struggle and vulnerability in art, real life, or online is a mixed bag. Case and point: the increasingly common phenomenon of filming yourself crying and posting it online. Perhaps unsurprisingly, those who do so are often labelled attention-seeking, narcissists, or performative.

A counterpoint to the carefully curated “highlight reel” that showcases only life’s best moments, crying online ostensibly presents a more honest and authentic self-portrait.

But for all the tear-streaked sharing (or oversharing, depending on who you ask) that happens on TikTok and Instagram, there are observers who can’t fathom what would possess someone in the throes of an emotional episode to pull out their phone and press record: How upset are you really, the insinuation goes, if your impulse in that moment is to turn your pain into content?

— Why People Post Themselves Crying Online, Harmeet Kaur, CNN (2025)

Is the raw portrayal of struggle online self-flagellation, the endless quest for external validation, or an earnest plea for connection and authenticity?

In a recent article by The Atlantic titled, “Beware the Weepy Influencer,” writer and psychologist Maytal Eyal takes a more cynical stance.

“They’re meant to inspire empathy, to reassure viewers that influencers are just like them. But in fact, they’re exercises in what I’ve come to call ‘McVulnerability,’ a synthetic version of vulnerability akin to fast food: mass-produced, easily accessible, sometimes tasty, but lacking in sustenance. True vulnerability can foster emotional closeness. McVulnerability offers only an illusion of it.”

If we are not sharing our vulnerabilities when talking about our lives (on- or off-line), then surely a highlight reel-like existence that perpetuates unrealistic expectations will remain the status-quo?

Although, perhaps that is what the collective now seeks. “We don’t need authenticity anymore, just give us great fiction,” is the general sentiment of today’s consumers according to

, Brand Strategy Consultant and Lecturer at the University of Melbourne, in his latest TikTok. Eugene’s argument rests on the premise that consumers are burnt out from brands’ abuse of ‘authenticity commodification’ and that, instead of pretending to be your bestie while convincing you to buy shit you don’t need, brands need to offer spectacle and reprieve, giving consumers something to dream about. I don’t disagree.However, I ponder whether, as online personhood becomes increasingly conflated with brandhood (“niche down”, “find your unique selling point”, over-insistence on “personal brand” and style, et cetera), Eugene’s diagnosis might even extend to content creators. It is not a far stretch to imagine that we have grown so tired of seeing struggle in our everyday lives— in news headlines, in growing inner-city homelessness, in international relations, in Palestine, in the absence of eggs in supermarkets, in the inability to afford olive oil— that we are consensually putting the blinders on and seeking content that only shows the pretty parts. Ignorance may be the only source of bliss when all the world is suffering. (That is an uncharacteristically gloomy thought, and not one I truly believe in. I think we still crave authenticity from friends, strangers, and online personalities, even those who present themselves as brands).

Heading into (what I’m praying will be short-term) unemployment, I am already wondering how I will answer the inevitable “What do you do?” that barges its way into every surface-level conversation in New York. Will I still adhere to the romcom-leading-lady tone I’ve always quietly loved to channel or will I go full sad-girl-lit-fic and embrace rawness? Does it have to be either/or?

Struggle without glamour is embarrassing, but so is inauthenticity. What about romanticism? Where does the moral quandary sit on the romanticisation of one’s life? I quite firmly assert that the two should not be confused. To romanticise your life is to find poetry in the everyday and the joy in the little things, while to glamorise is to modify all with a culturally seductive filter.

[Glamour is] not just style or a personal quality but a phenomenon that reveals our inner lives and shapes our decisions, large and small. By embodying the promise of a different and better self in different and better circumstances, glamour stokes ambition and nurtures hope, even as it fosters sometimes-dangerous illusions.

— Blurb from The Power of Glamour: Longing and the Art of Visual Persuasion Hardcover by Virginia Postrel (2013)

Against what then, should I measure myself to relativise my success? I want to be honest that living abroad, unemployment, and life in general can be really hard work, but I also don’t want to present a self mired in hardship (as that would be equally inaccurate).

If you want to move to New York or London or Paris to be a writer or fashion stylist or artist or whatever it may be, that’s great!! But do so knowing that it is unlikely to resemble the vast majority of media you’ve consumed portraying such a life. Somewhere between DIMLs, romcoms, and sad girl literary fiction, we have the contemporary truth. All at once, this experience is likely to be messy and chaotic and exhilarating and organised and inspiring and exasperating and exhausting and alienating and joyful and heartbreaking and imperfect. (Imagine that).

All of this to say, I am as guilty as the next woman of glamorising the lives of those around me based on whichever highlight reel, LinkedIn post, or curated photo dump crosses my radar. There is a synthetic tendency to share only the brightest, best parts of your life online, and if not the brightest and the best, then at least the coolest and the most curated. Let this be your reminder to take everything you consume online, especially regarding other people’s lives, with a pinch of salt. In my view, the best we can do is acknowledge the imperfection and rollercoaster-like ways of our human existence, and treat any temptation to glamorise with a healthy dose of wariness.

I am so proud of and in love with the life I am building, and it is (and will always be) far from perfect and occasionally punctuated with unglamorous difficulties. All things that can be true at once.

(Isn’t that the whole point?)

yes!! i totally agree, and you said this so well. there is definitely an art in romanticizing the "ugly" parts of our lives, and part of it is probably some sort of coping mechanism. i think without glamorizing the struggle, our lives would be much more miserable. the distinct change in perspective can really make all the difference.

I discovered your Substack not so long ago and I love it!!!